At the core of the mystique surrounding Kala Sarpa is the existential question: is it a yoga, or is it a dosha? Does it promise success or threaten destruction?

At the core of the mystique surrounding Kala Sarpa is the existential question: is it a yoga, or is it a dosha? Does it promise success or threaten destruction?

That question can only be answered via yoga vichara, the careful analysis of a configuration in order to determine its nature, its strength, and its ultimate import. Although such analysis is de rigueur for any practicing jyotishi, such is not the scope of this article. Here, I wish only to present some recent findings regarding the astronomical realities of Kala Sarpa in the birth chart, and how some of them have a bias for the notion of dosha.

The formation of Kala Sarpa in a chart has consequences. By definition, the chart is split in two by the nodal axis, and all of the planets constrained to roughly half of the zodiac. I say âroughlyâ because there are four classes of Kala Sarpa: two in which the planets must occupy only the five intervening signs between nodes, and another two classes in which planets may occupy the same sign as either or both nodes. For those unfamiliar with the definitions of these four classes, see this article on my website.

Over the past year and a half, while conducting research into Kala Sarpa, I examined 600 such charts â over 200 famous persons, and almost 400 clients from my own files. My analysis of their commonalities and differences produced some startling conclusions, all of which are covered in my recent book.

For this article, however, I want to focus on just three astronomical phenomena that are modified by the formation of a Kala Sarpa in the horoscope. Their occurrences in turn influence the avasthas of the planets, whose strength or weakness are germane in assessing the overall tenor of a chart. These astronomical factors are: lunar phase, combustion, and retrogression.

Lunar phase

Unlike the Sun, the Moon doesnât emit light of its own. We see it with the naked eye only because sunlight reflects off the lunar surface. As the Moon revolves around Earth, it goes through apparent phases. When in the same part of the sky as the Sun, itâs mostly invisible because sunlight canât reflect off that half of the Moon facing us. But as the Moon advances through the zodiac, we see a crescent of sunlight reflected from its surface. The greater its angular separation from the Sun, the more Moon we see in its waxing phase. When from our perspective the Moon is opposite the Sun we see it as full. As the Moon closes the angular distance from the Sun, we see a diminishing crescent in its waning cycle until it seems to disappear completely in the Sunâs aura.

A âdark moonâ is one whose light is minimal, ie, when the Moon is in the same or adjacent sign to the Sun. Conversely, a âbright moonâ is one whose light is at or near maximum, ie, when the Moon is in the opposite, or next-to-opposite sign from the Sun. Under Kala Sarpa conditions, bright moons are infrequent because the two luminaries canât be opposed unless both are close to opposite nodes. Conversely, dark moons are more frequent under Kala Sarpa when the two luminaries are restricted to just half the zodiac.

When we count signs inclusively from one luminary to another, a Full Moon occurs when the reciprocal count (from one to the other, in either direction) is 7/7, but the Moon is still bright, or âfullish,â when the count is 6/8. On the other hand, a New Moon occurs when the count is 1/1, but the Moon is still dark, either waxing or waning, when the count is 2/12.Â

Graph 1 illustrates the difference between lunar phases in the average chart versus a Kala Sarpa chart. Note that a New Moon (1/1) occurs in only one relative sign out of 12 (8.3%) while the same is true for Full Moon (7/7). For the other phase relationships â 2/12, 3/11, 4/10, 5/9 and 6/8 â the chances are two relative signs out of 12 (16.7%), because there are both waxing and waning phases.

From this graph we see that Kala Sarpa charts have a bias for âdark Moonâ charts as opposed to âbright Moonâ charts. Thus, natives with Kala Sarpa charts generally lack one source of planetary strength, ie, a bright Moon. Since the Moon is the karaka for the manas (the sensory mind), this suggests a disposition for dysfunctionality of some kind â mental, emotional, and/or physical â that may afflict the native for a lifetime.

Here is the first piece of âastro-logicalâ evidence (based on astronomy) that substantiates Kala Sarpaâs general perception as dosha rather than yoga.

Combustion

Combustion occurs when one of the true planets (Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus, or Saturn) appears so close to the Sun that the solar corona eclipses the visibility of that planet. Shastra stipulates individual orbs of combustion for each of the planets, in both direct and retrograde motion. For functional purposes, however, many astrologers use a simple classification for all planets: total combustion within three degrees of orb, moderate combustion at three to six degrees, and mild combustion at six to nine degrees.

Under this latter definition, letâs consider total combustion for the planets. For instance, how often will Mars be within three degrees of the Sun? The answer: given three degrees on one side, and three degrees on the other, thatâs a combined range of six degrees out of 360 (1/60), or 1.66% of the time. Without trying to factor in the effects of retrogression, we can say this is likewise true of the other two outer planets, Jupiter and Saturn, who enjoy âuncoupledâ movement with respect to the Sun.

With the inner planets, the odds are different. From Earthâs perspective, Mercury and Venus are always in the Sunâs general vicinity, Mercury never more than 28 degrees away from the Sun, Venus never more than 48 degrees away. Again ignoring retrogression, we estimate Mercury will be totally combust, in six degrees of its 56-degree range (28 degrees on either side), for 10.7% of the time. Similarly, Venus is totally combust, in six degrees of its 96-degree range (48 degrees on either side), for 6.25% of the time.

Based on these parameters, we can calculate that for any large but random group of charts, 22.0% of them will have a combust planet. However, if we restrict our consideration only to Kala Sarpa charts, 25.7% of them will have a combust planet. Again, these percentages are approximate, and are based on a relatively simplistic model.

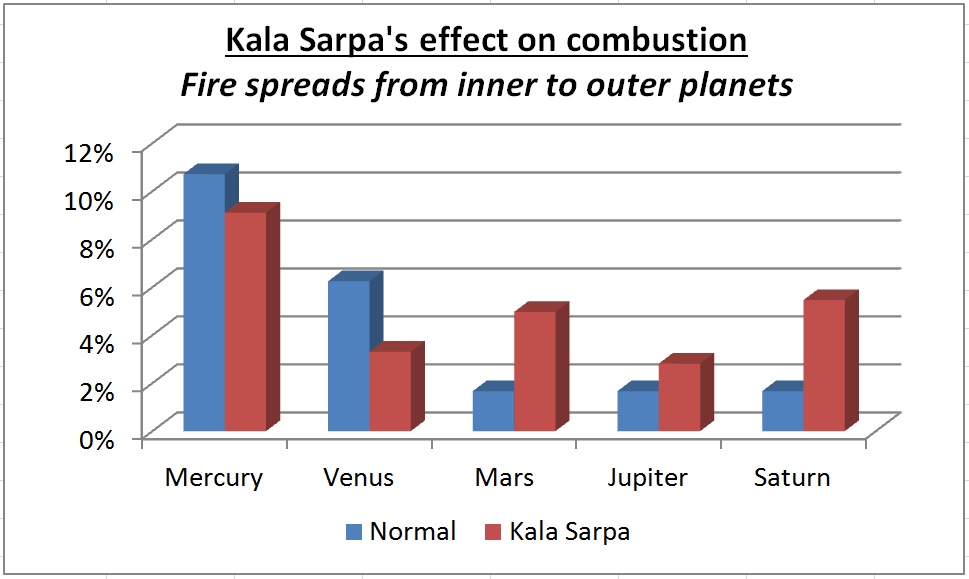

However, working with my database of over 600 Kala Sarpa charts, I tabulated the actual frequency of total combustion (3-degree orb) for the true planets: Mercury 9.1%, Venus 3.3%, Mars 5.0%, Jupiter 2.8%, and Saturn 5.5%. But when I compared the theoretical frequencies of combustion for the average chart (see discussion above) versus the observed frequencies in Kala Sarpa charts, I found a significant variance, as shown in Graph 2.

Because Kala Sarpa restricts the outer planets to roughly half of the zodiac, this dramatically increases the chances of Mars, Jupiter and Saturn becoming totally combust. However, the diminished frequency of combustion among the inner planets obviously requires further analysis.

Because Kala Sarpa restricts the outer planets to roughly half of the zodiac, this dramatically increases the chances of Mars, Jupiter and Saturn becoming totally combust. However, the diminished frequency of combustion among the inner planets obviously requires further analysis.

In any event, the net effect remains the same â in the presence of Kala Sarpa, combustion is overall more prevalent, and this weakens the true planets. Again, this substantiates the notion of Kala Sarpa as dosha, since it vitiates one of the key planetary avasthas.

Retrogression

In Jyotisha, a retrograde planet acquires strength by virtue of its relative brightness, which is greater during its retrogression phase.

All planets revolve around the Sun from west to east, in what is called their direct motion. Because the Earth moves at a different speed than the other planets, it appears to overtake the superior (outer) planets, meanwhile being overtaken by the inferior (inner) planets. From Earth, those other planets periodically appear to slow down, stop, and reverse their direction against the backdrop of the zodiac. When a planet appears to move backwards, itâs said to be retrograde, or in a state of retrogression.

Based on observation, the average proportion of time planets are retrograde is: Mercury 19.2%, Venus 7.2%, Mars 9.5%, Jupiter 30.2%, and Saturn 36.4%. At any given time, one planet or another will often be retrograde. Roughly 70% of charts have a retrograde planet. Thus, the vast majority of charts have at least one strong planet due to retrogression.

However, once we shift our analysis to Kala Sarpa charts, the observed frequency of retrogression is subject to radical change, with certain qualifications.

We donât expect to see much difference in the retrogression of inner planets, with or without Kala Sarpa. Thatâs because Mercury and Venus are only retrograde when theyâre nearest the Earth. And when that happens, theyâre usually in the same or adjacent sign as the Sun.

But with the outer planets, retrogression only occurs when theyâre at least five signs away from the Sun. Note: this doesnât mean outer planets opposing the Sun are always retrograde; it only means that when outer planets do go retrograde, theyâre always on the other side of the chart, not necessarily opposite the Sun, but generally five or more signs removed from it.

So in a Kala Sarpa chart, if the Sun is in the 1st house, and the nodal axis is in the 4th/10th, the outer planets canât be retrograde because theyâre on the same side of the nodal axis as the Sun.

Assume the nodes remain in the 4th/10th, but the Sun moves to the 3rd house. Now the outer planets could be on the other side of the chart, say the 10th or 11th, therefore possibly retrograde while still within the Kala Sarpa. But they canât be in the 7th, 8th or 9th houses, on the wrong side of the nodal axis. In this example, roughly half of the outer planetsâ arc of retrogression would be eliminated under Kala Sarpa.

Based on my analysis of over 600 charts, the observed frequency of retrograde planets under those limits is: Mercury 20.2%, Venus 6.5%, Mars 3.3%, Jupiter 11.4%, and Saturn 16.1%. But when I compared the observed frequency of retrogrades in normal charts vs that observed in Kala Sarpa charts, I found another major variance, as shown in Graph 3.

The astronomical limits imposed by Kala Sarpa therefore restrict the retrogression of outer planets. Consequently, whereas 70% of normal charts have at least one retrograde planet, only 45% of Kala Sarpa charts have a retrograde planet. Again, this is further evidence of Kala Sarpaâs capacity to diminish yet another planetary avastha, thus vitiating the potential strength of a chart, reducing its chances of manifesting yoga as opposed to dosha.

The astronomical limits imposed by Kala Sarpa therefore restrict the retrogression of outer planets. Consequently, whereas 70% of normal charts have at least one retrograde planet, only 45% of Kala Sarpa charts have a retrograde planet. Again, this is further evidence of Kala Sarpaâs capacity to diminish yet another planetary avastha, thus vitiating the potential strength of a chart, reducing its chances of manifesting yoga as opposed to dosha.

Kala Sarpa: a mixed blessing

As we saw in this article, the crowding of planets into roughly half the zodiac restricts both the brightness of the Moon and that of the true planets by curtailing, respectively, its lunation cycle and their retrogression phases. Similarly, because Kala Sarpa forces the planets into proximity, it increases the chances of combustion, another astronomical phenomenon that compromises the avasthas of the true planets.

Thus, we can see that Kala Sarpa deserves at least some of its reputation for dosha-like consequences, because it has the potential to vitiate the avasthas of the planets. But as Iâll discuss in next monthâs article, Kala Sarpa also has its upside, astronomically-speaking, in the formation of other yogas.

Although none of this is complicated, neither was it obvious until subjected to analysis. Once weâre aware of it, however, we must acknowledge that Kala Sarpa is a complex phenomenon. At best, it might be viewed as a mixed blessing. The challenge, as always, is to assess these diverse and sometimes contradictory indications in order to determine a likely prognosis for the life of the native whose chart contains a Kala Sarpa.

~~~

Alan Annand studied with Hart de Fouw, and is a graduate of the American College of Vedic Astrology and a former tutor for the British Faculty of Astrological Studies.

He is the author of several non-fiction books. Kala Sarpa is a first-of-its-kind reference book on a unique pattern in jyotisha that is not discussed in shastra yet is part of Indiaâs rich oral tradition. Stellar Astrology, Volumes 1 & 2, offer a wealth of time-tested techniques in the form of biographical profiles, analyses of world events, and technical essays. Parivartana Yoga is a reference text for one of the most common yet powerful planetary combinations in jyotisha. Mutual Reception is an expanded companion volume for western practitioners, covering the same subject of planetary exchange through the lens of traditional astrology.

He is the author of several non-fiction books. Kala Sarpa is a first-of-its-kind reference book on a unique pattern in jyotisha that is not discussed in shastra yet is part of Indiaâs rich oral tradition. Stellar Astrology, Volumes 1 & 2, offer a wealth of time-tested techniques in the form of biographical profiles, analyses of world events, and technical essays. Parivartana Yoga is a reference text for one of the most common yet powerful planetary combinations in jyotisha. Mutual Reception is an expanded companion volume for western practitioners, covering the same subject of planetary exchange through the lens of traditional astrology.

His New Age Noir crime novels (Scorpio Rising, Felonious Monk, Soma County) feature astrologer and palmist Axel Crowe, whom one reviewer has dubbed âSherlock Holmes with a horoscope.â

Websites: www.navamsa.com, www.sextile.com

You can find his books on Amazon, Apple, Barnes&Noble, Kobo and Smashwords.

I have a chart where only lagna is out of the nodal axis,rahu is conjunct Mars in Gemini,the other planets distributed from cancer to libra….interesting thing is that rahu and ketu are in their own nakshatras…..so i think that rahu and ketu in its own nakshatras make this ks super strong…..what do u think?

Technically, the presence of MA on the RKA injects a bit of dosha, but it depends on what else is going on. However, with both RA and KE swa nakshatra, this certainly does amplify the yoga.